Rhyolite Sign about 2009

The Rhyolite historic townsite, maintained by the Bureau of Land Management, is "one of the most photographed ghost towns in the West". It is outside of Death Valley National Park. Ruins include the railroad depot and other buildings, and the Bottle House, which the Famous Players Lasky Corporation, the parent of Paramount Pictures, restored in 1925 for the filming of a silent movie, The Air Mail.

The ruins of the Cook Bank Building were used in the 1964 film The Reward and again in 2004 for the filming of The Island. Orion Pictures used Rhyolite for its 1987 science-fiction movie Cherry 2000 depicting the collapse of American society. Six-String Samurai (1998) was another movie using Rhyolite as a setting.

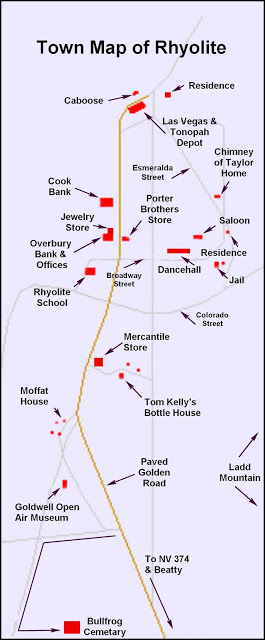

When I first visited the mining ghost town of Rhyolite in 1959, as a sidelight of my Death Valley trip, it was a mix of private land and federal land managed by the Bureau of Land Management (BLM). Some privately owned buildings were maintained by the owners. Rhyolite has since been designated as the Rhyolite Historic Area and the BLM has taken more active management of the buildings on federal government land including placing signs identifying buildings, etc. I later made a brief visit in 1998.

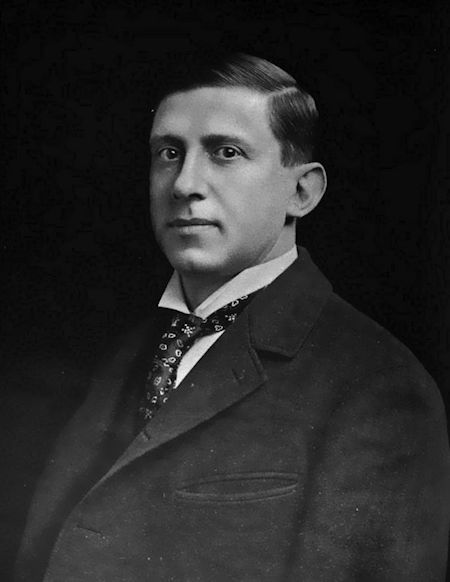

Charles M. Schwab, 1901

Rhyolite is a ghost town in Nye County, Nevada in the Bullfrog Hills, about 120 miles northwest of Las Vegas, near the eastern edge of Death Valley. The town began in early 1905 as one of several mining camps that sprang up after a prospecting discovery in the surrounding hills.

During an ensuing gold rush, thousands of gold-seekers, developers, miners and service providers flocked to the Bullfrog Mining District. Many settled in Rhyolite, which lay in a sheltered desert basin near the region's biggest producer, the Montgomery Shoshone Mine.

The town is named for rhyolite, an igneous rock composed of light-colored silicates, usually buff to pink and occasionally light gray. It belongs to the same rock class, felsic, as granite but is much less common.

Industrialist Charles M. Schwab bought the Montgomery Shoshone Mine in 1906 and invested heavily in infrastructure, including piped water, electric lines and railroad transportation, that served the town as well as the mine.

By 1907, Rhyolite had electric lights, water mains, telephones, newspapers, a hospital, a school, an opera house, and a stock exchange. Published estimates of the town's peak population vary widely, but scholarly sources generally place it in a range between 3,500 and 5,000 in 1907–08.

Rhyolite declined almost as rapidly as it rose. After the richest ore was exhausted, production fell. The 1906 San Francisco earthquake and the financial panic of 1907 made it more difficult to raise development capital.

In 1908, investors in the Montgomery Shoshone Mine, concerned that it was overvalued, ordered an independent study. When the study's findings proved unfavorable, the company's stock value crashed, further restricting funding.

By the end of 1910, the mine was operating at a loss, and it closed in 1911. By this time, many out-of-work miners had moved elsewhere, and Rhyolite's population dropped well below 1,000. By 1920, it was close to zero.

After 1920, Rhyolite and its ruins became a tourist attraction and a setting for motion pictures. Most of its buildings crumbled, were salvaged for building materials, or were moved to nearby Beatty or other towns, although the railway depot and a house made chiefly of empty bottles were repaired and preserved.

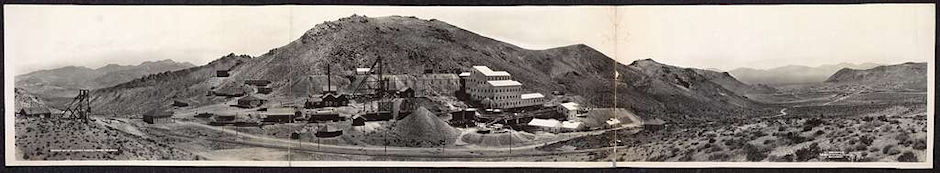

Montgomery Shoshone Mine Jan 1908 - Rhylolite is in the distance on the right

Montgomery Shoshone Mine 1908

"Bullfrog" was the name Frank "Shorty" Harris and Ernest "Ed" Cross, the prospectors who started the Bullfrog gold rush, gave to their mine. As quoted by Robert D. McCracken in A History of Beatty, Nevada, Harris said during a 1930 interview for Westways magazine, "The rock was green, almost like turquoise, spotted with big chunks of yellow metal, and looked a lot like the back of a frog."

On August 9, 1904, Cross and Harris found gold on the south side of a southwestern Nevada hill later called Bullfrog Mountain. Assays of ore samples from the site suggested values up to $3,000 a ton, or about $85,000 a ton in 2019 dollars when adjusted for inflation. Word of the discovery spread to Tonopah and beyond, and soon thousands of hopeful prospectors and speculators rushed to what became known as the Bullfrog Mining District.

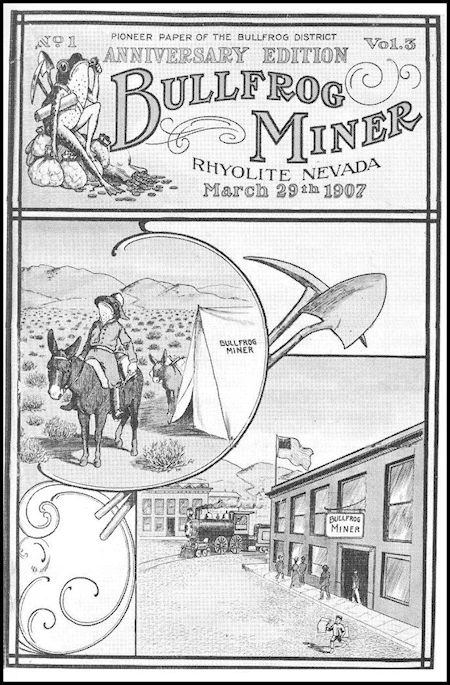

Bullfrog Miner Newspaper, 1907

Within the district, gold rush settlements quickly arose near the mines, and Rhyolite became the largest. It sprang up near the most promising discovery, the Montgomery Shoshone Mine, which in February 1905 produced ores assayed as high as $16,000 a ton, equivalent to $455,000 a ton in 2019.

Starting as a two-man camp in January 1905, Rhyolite became a town of 1,200 people in two weeks and reached a population of 2,500 by June 1905. By then it had 50 saloons, 35 gambling tables, cribs for prostitution, 19 lodging houses, 16 restaurants, half a dozen barbers, a public bath house, and a weekly newspaper, the Rhyolite Herald. Four daily stage coaches connected Goldfield, 60 miles to the north, and Rhyolite. Rival auto lines ferried people between Rhyolite and Goldfield and the rail station in Las Vegas in Pope-Toledos, White Steamers, and other touring cars.

Ernest Alexander "Bob" Montgomery, the original owner, and his partners sold the Montgomery Shoshone Mine to industrialist Charles M. Schwab in February 1906. Schwab expanded the operation on a grand scale, hiring workers, opening new tunnels and drifts, and building a huge mill to process the ore. He had water piped in, paid to have an electric line run 100 miles from a hydroelectric plant at the foot of the Sierras to Rhyolite, and contracted with the Las Vegas and Tonopah Railroad to run a spur line to the mine.

Las Vegas and Tonopah Railroad Station - Rhyolite - Jan 1959

Three railroads eventually served Rhyolite. The first was the Las Vegas and Tonopah Railroad (LVTR), which began running regular trains to the city on December 14, 1906. Its depot, built in California-mission style, cost about $130,000, equivalent to about $3,700,000 in 2019. In the 1930s, the old depot became a casino and bar, and later it became a small museum and souvenir shop that stayed open into the 1970s.

About a half-year later, the Bullfrog Goldfield Railroad (BGR) began regular service from the north. By December 1907, the Tonopah and Tidewater Railroad (TTR) began service to Rhyolite on tracks leased from the BGR. The TTR was built to reach the borax-bearing colemanite beds in Death Valley as well as the gold fields.

The town citizens had an active social life including baseball games, dances, basket socials, whist parties, tennis, a symphony, Sunday school picnics, basketball games, Saturday night variety shows at the opera house and pool tournaments. In 1906 Countess Morajeski opened the Alaska Glacier Ice Cream Parlor to the delight of the local citizenry.

In April 1907 electricity came to Rhyolite, and by August of that year a mill had been constructed to handle 300 tons of ore a day at the Montgomery Shoshone mine. It consisted of a crusher, 3 giant rollers, over a dozen cyanide tanks and a reduction furnace. The Montgomery Shoshone mine had become nationally known because Bob Montgomery once boasted he could take $10,000 a day in ore from the mine.

By 1907, about 4,000 people lived in Rhyolite, according to Richard E. Lingenfelter in Death Valley & the Amargosa: A Land of Illusion. Russell R. Elliott cites an estimated population of 5,000 in 1907–08 in Nevada's Twentieth-Century Mining Boom, noting that "accurate population figures during the boom are impossible to obtain".

Alan H. Patera in Rhyolite: The Boom Years states published estimates of the peak population have been "as high as 6,000 or 8,000, but the town itself never claimed more than 3,500 through its newspapers". The newspapers estimated that 6,000 people lived in the Bullfrog mining district, which included the towns of Rhyolite, Bullfrog, Gold Center, and Beatty as well as camps at the major mines.

Rhyolite in 1907 had concrete sidewalks, electric lights, water mains, telephone and telegraph lines, daily and weekly newspapers, a monthly magazine, police and fire departments, a hospital, school, train station and railway depot, at least three banks, a stock exchange, an opera house, a public swimming pool and two formal church buildings.

The financial panic of 1907 took its toll on Rhyolite and was seen as the beginning of the end for the town. In the next few years mines started closing and banks failed. Newspapers went out of business, and by 1910 the production at the mill had slowed to $246,661 and there were only 611 residents in the town.

In February 1908, a committee of minority stockholders, suspecting that the mine was overvalued, hired a British mining engineer to conduct an inspection. The engineer's report was unfavorable, and news of this caused a sudden further decline in share value from $3 to 75 cents.

Schwab expressed disappointment when he learned that "the wonderful high-grade [ore] that had brought [the mine] fame was confined to only a few stringers and that what he had actually bought was a large low-grade mine."

Although the mine produced more than $1 million (equivalent to about $24 million in 2009) in bullion in its first three years, its shares declined from $23 a share (in historical dollars) to less than $3.

Although the mine was still profitable in 1908, by 1909 no new ore was being discovered, and the value of the remaining ore steadily decreased. In 1910, the mine operated at a loss for most of the year, and on March 14, 1911 the directors voted to close down the Montgomery Shoshone mine and mill. By then, the stock, which had fallen to 10 cents a share, slid to 4 cents and was dropped from the exchanges.

In 1916 the light and power were finally turned off in the town.

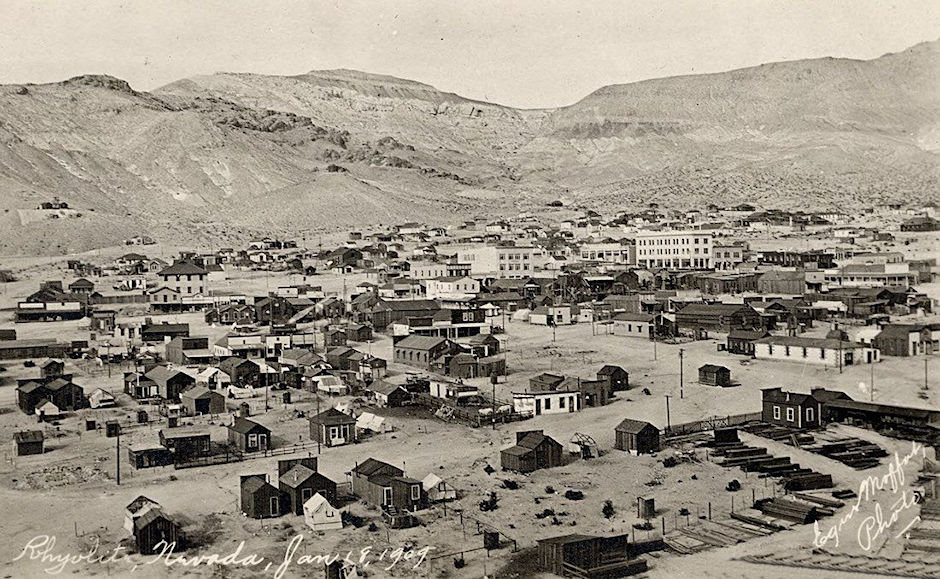

Rhyolite, January 18, 1909

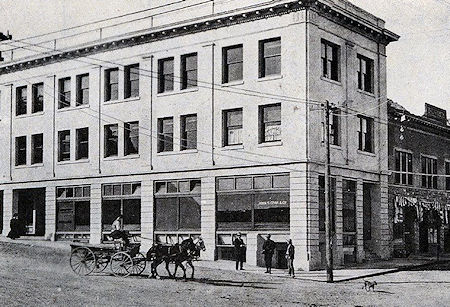

Of the many buildings in Rhyolite, the most prominent was the three-story John S. Cook and Co. Building on Golden Street. Finished in 1908, it cost more than $90,000, equivalent to $2,560,000 in 2019. It was the largest building in town, with two vaults, Italian marble floors, imported stained-glass windows, mahogany woodwork, electric lights, running water, telephones and indoor plumbing.

The first floor housed the Bank of John S. Cook & Company which was first established in 1905 by John S. Cook, as a private bank, with a capital of $50,000. It was shortly absorbed by the First National Bank of Rhyolite, Nevada.

Brokers' offices utilized most of the second and third floors, while the town's post office occupied the basement. The post office was the last business to leave the town in 1919.

John S. Cook and Co. Bank Building - Rhyolite - Jan 1959

John S. Cook and Co. Bank Building - Rhyolite - Jan 1959

John S. Cook and Co. Bank Building - Rhyolite - Nov 1998

John S. Cook and Co. Bank Building 1909

John S. Cook and Co. Bank Building 1923

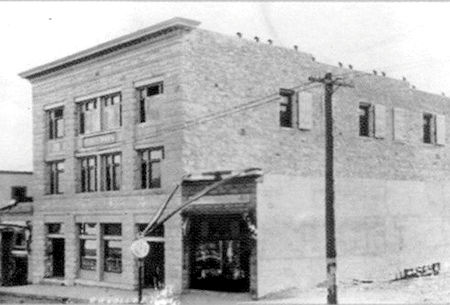

Another large building was the three-story Overbury Building located on Golden Street midway between Broadway and Colorado across from the Porter Store. In 1907, Rhyolite resident John Overbury returned from a trip to Europe and built one of the most modern buildings in the west at a cost of $45,000.

It was built of rock and concrete and had modern plumbing, fire plugs and fire hoses on every floor, electric wiring and a 5,000 gallon water tank on the roof. The stone was cut from a quarry just north of town. It housed more than 25 elegant offices. The First National Bank of Rhyolite, Nevada was housed in the Overbury Building prior to re-locating in the John S, Cook & Co. building a year later. The building next door housed a jewelry store.

Note: After the town was deserted, a mining company came in and took the stones of the Overbury Building and ground them up to fine power to get the gold out. That's one of the reasons it is in even worse shape than the rest.

Overbury Building - Rhyolite - Jan 1959

Overbury Building with Jewelry Store next door

Another building housed the Rhyolite Mining Stock Exchange, which opened on March 25, 1907, with 125 members, including brokers from New York, Philadelphia, Los Angeles, and other large cities. The small, modestly equipped storefront listed shares of 74 Bullfrog companies and a similar number of companies in nearby mining districts. Sixty thousand shares changed hands on the first day, and by the end of the second week the number had topped 750,000.

The second store the Porter Brothers built in Rhyolite in 1906 sold mining supplies, food and bedding. The building once had large glass windows to make it easy for people to see what they had for sale. The Porter Brothers were old pros at selling things during gold rushes. Along with the one in Rhyolite, they opened stores in the nearby towns of Ballarat, Beatty, and Pioneer.

Like the town itself, the Porter brothers' store was short-lived, opening in 1902 and closing it in 1910. After that, H.D. Porter became the local postmaster and stayed in town until 1919.

Porter Brothers Store - Rhyolite - Jan 1959

Porter Brothers Store - Rhyolite - Nov 1998

Rhyolite Bottle House by Aimless Adventures 2017

One of America's most peculiar ghost towns, Rhyolite, Nevada is uniquely rich in one thing: bottle houses. Three of these structures–made by embedding glass beverage bottles in various kinds of mortar–can be found in this long-dead desert town.

A marvel in its own right, the standout among these glass houses was built by a man named Tom Kelly. Like so many others, Kelly had been drawn to the West by the promise of gold. Around the year 1905, Kelly chose Nevada's Bullfrog Hills as the site where he would finally put down his pan and build a home. In the mining camp of Rhyolite, where the only source of lumber was the ill-suited Joshua tree, Kelly saw construction potential at the bottom of his beer bottle.

With an estimated 50 saloons operating in Rhyolite at the time, Kelly collected 50,000 bottles in less than six months, enough to build a three-room house, complete with a porch and quaint gingerbread trim. Inside, the walls were plastered like a real city home. To miners of the day, this was a castle.

Already approaching 80 years old, Kelly declined to live in the home he'd built, and instead capitalized on the hubbub. Upon its completion in February of 1906, Kelly raffled off the bottle house for $5 per ticket. The house was won by the Bennet family, who lived inside until 1914.

By 1920, the boomtown had gone bust, and a mere 20 residents remained in Rhyolite. In 1925, the bottle house got a facelift in the form of a new roof when Paramount Pictures used it for a movie set. It was converted into a museum of sorts after filming.

From 1936 until 1954, Lewis Murphy was the Bottle House's resident caretaker, providing tours for all interested visitors. After his departure, the bottle house's next inhabitants were Tommy Thompson and his family, including eight children, who lived there until 1969 and added the miniature houses like the one that can be seen on the lawn in the 1959 picture below and in the video above.

The above text adapted from this Tom Kelly's Bottle House website which has numerous fairly recent pictures.

Tom Kelly Bottle House - Rhyolite - Jan 1959

Tom Kelly Bottle House - Rhyolite - Nov 1998

The Rhyolite School was erected in 1909. This was Rhyolite's second school. Rhyolite built its first school early in 1906 and the enrollment soon reached 90. The first school was a wooden building that blew down in a severe wind storm. In the meantime they used the County Hospital to house the school until they decided what to do. By May 1907 the number of students reached 250.

After the approving of a $20,000 school bond, this modern new two-story schoolhouse was built with eight classrooms and an auditorium and a galvanized Spanish tile roof and a bell copula. Constructed of fireproof concrete, it was completed in January of 1909. However, by the time it was built, most of the students had left Rhyolite and the town was already becoming a ghost town. It was only used for about a year.

The spacious upstairs later functioned as a meeting hall, for socials and anything that needed a large room. Eventually the roof tiles, windows, and interior wood went to the middle school in Beatty.

Rhyolite School (left), Cook Bank (center), Porter Store (right)

Rhyolite - Jan 1959

Rhyolite Jail - Rhyolite - Jan 1959

House in Rhyolite - Rhyolite - Jan 1959

The Rhyolite-Bullfrog cemetery, with many wooden headboards,

is slightly south of Rhyolite - Rhyolite - Jan 1959

Rhyolite began to decline before the final closing of the mine. At roughly the same time that the Bullfrog mines were running out of high-grade ore, the 1906 San Francisco earthquake diverted capital to California while interrupting rail service, and the financial panic of 1907 restricted funding for mine development.

As mines in the district reduced production or closed, unemployed miners left Rhyolite to seek work elsewhere, businesses failed, and by 1910, the census reported only 675 residents. All three banks in the town closed by March 1910. The newspapers, including the Rhyolite Herald, the last to go, all shut down by June 1912.

The post office closed in November 1913; the last train left Rhyolite Station in July 1914, and the Nevada-California Power Company turned off the electricity and removed its lines in 1916. Within a year the town was "all but abandoned", and the 1920 census reported a population of only 14. A 1922 motor tour by the Los Angeles Times found only one remaining resident, a 92-year-old man who died in 1924.

Much of Rhyolite's remaining infrastructure became a source of building materials for other towns and mining camps. Whole buildings were moved to Beatty. The Miners' Union Hall in Rhyolite became the Old Town Hall in Beatty, and two-room cabins were moved and reassembled as multi-room homes. Parts of many buildings were used to build a Beatty school.

Rhyolite, Nevada - The Ghost Town by Cruise Monkey 2016

Rhyolite, Nevada by 3zooz Q8i 2015

There are numerous websites containing history and pictures about Rhyolite. Some of these were the source of some of the text information above: