The Elkhorn Mine property is privately owned. The Coolidge Ghost Town is on Forest Service land managed by the Beaverhead-Deerlodge National Forest and is protected as a National Historic Site. It is accessible via a 1/4 mile hike from the end of the road.

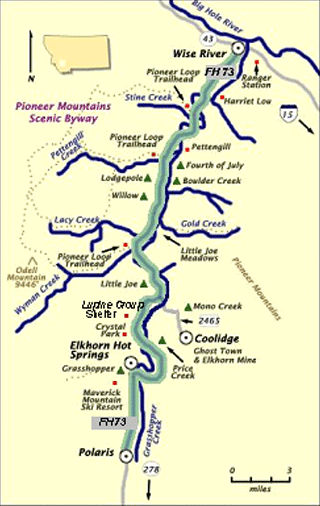

The Pioneer Mountains Scenic Byway (PDF) guides you to the area and contains historical information.

The following is adapted from an article on the Montana Department of Environmental Quality website.

Elkhorn Mine and Mill

The Elkhorn mining district is located in the Pioneer Mountains northwest of Comet Mountain at the headwaters and on the divide of Wise River and Grasshopper Creek. The central group of claims is at an elevation of 7,000 to 8,000 feet above sea level about four miles northeast of Elkhorn Hot Springs on the west side of the East Fork of Wise River.

A decade after the first gold strikes in southwestern Montana, a number of mining districts in the Pioneer range became major silver producers, but Elkhorn with all its activity and notoriety was not among them. In general the ores of this district are of low grade, but the veins are large.

The first discovery of silver ore in the Elkhorn district was made by Preston Sheldon in 1872. He shipped a carload of the ore, assaying 300 ounces of silver to the ton, from a claim called the Old Elkhorn, located about a mile southwest of later Coolidge/Elkhorn townsite and mine.

In 1874, Mike T. Steele located the Storm claim -- adjacent to the west side of the Old Elkhorn claim -- and shipped two carloads of ore, assaying 260 ounces of silver to the ton.

During the next twenty years a number of claims were located and successfully mined.

Mining operations were severely restricted throughout southwestern Montana by the lack of economical transportation prior to 1882. In order to be smelted, the ore had to be hauled by wagon to Corinne, Utah and then sent by railroad to San Francisco and from there by ship to Swansea, Wales where the smelters were located.

Obviously only high-grade ore could be sent on this long, circuitous route to the smelters. In spite of this serious handicap, a number of mines in the district did manage to operate profitably on a small scale during the 1870s.

In the 1880s more mines went into operation following the completion of the Utah and Northern railroad to Silver Bow in December of 1881.

In 1893, however, silver prices crashed and all the mining operations throughout the district closed down for the next decade, except for a small amount of prospecting work.

In the twentieth century, virtually all mining activity in the district was centered on the Elkhorn lode. The massive operation to develop the lode would turn out to be one of Montana's last and largest silver mining ventures.

The development, operation and ultimate failure of the Elkhorn project is illustrative of the lures and pitfalls of many similar large-scale mining operations which have come and gone in Montana during the past century.

The Elkhorn lode was located by Mike T. Steele and F. W. Pahnish on October 24, 1873. A partnership was formed with Con Bray and Judge Meade and enough money was raised to build a small mill on the site.

For the next two decades, small amounts of high-grade ore were mined and shipped to Swansea for smelting. In 1893, the Elkhorn shut down, along with the district's other mines, after the disastrous drop in silver prices that year.

By 1903, silver prices had recovered to a point where it seemed feasible to revive the Elkhorn mine. Tom Judge found a rich vein of silver ore while doing prospecting work on the Elkhorn Ledge. This generated some interest to reopen the mine, but there was not sufficient financing to get the project underway.

In 1906, Frank Felt bought a number of claims in the district and, along with M. L. McDonald and Donald B. Gillies, started a tunnel on the Idanha vein which eventually would become the major producing mine for the Elkhorn group.

Large-scale development of the Elkhorn lode got underway in 1911. William R. Allen, former lieutenant governor of Montana turned mining entrepreneur, became interested in the property and devoted his efforts to developing the Elkhorn mines on a scale which dwarfed anything attempted in the area before or since.

Allen would be inextricably linked with the fortunes of the Elkhorn mine for the next 40 years. Although many others were involved in the development of the Elkhorn mine, Allen was the chief promoter and prime mover of the project from beginning to end. His personal career and fortune would be mirrored in the development and ultimate failure of the Elkhorn mine project.

Although it seemed that Allen had a promising future in politics, he resigned as lieutenant governor in 1913 in order to devote all his efforts to the Elkhorn project. He demonstrated a talent for financial promotion and was able to interest financiers in London and Boston in the venture.

He helped form the Boston-Montana Development Corporation in 1913 and became its president. Eventually the corporation, under his leadership, would acquire some 80 mining claims, covering 1600 acres.

A wagon road had been built to the mines but it was obvious that a rail line would be needed.

Allen also formed the Boston-Montana Milling and Power Company to develop the mine and mill while another subsidiary - the Butte and Pacific Railway Company - was formed to construct a railroad line from the town of Divide on the Big Hole River to the mine.

Preliminary work on the rail line route was done in 1914 and heavy machinery for the mines was purchased but the outbreak of World War I delayed financing from the English backers.

Reincorporated as the Montana Southern Railway, construction of the line began in earnest in May 1917. Completed on November 1, 1919, the railroad ran westward from a connection with the Oregon Short Line Railroad at Divide, following the Big Hole River upstream to the town of Wise River, Montana, also known as Allentown.

From there, the railroad headed south into the Pioneer Mountains, terminating at the booming mining camp of Coolidge, where Boston-Montana had constructed a 750 ton per day oil flotation mill and other developments. In all, the line was about 38 miles long. The line was noteworthy in that it was the last common carrier narrow gauge railroad to be constructed in the United States.

The railroad was equipped with three Baldwin locomotives, 28 freight cars, three passenger cars, a machine shop, an engine house and depots at a total cost of $1,500,000 [J. R. Pelt, director of the Montana Bureau of Mines and Geology, in a letter to Mrs. Fannie Gold on August 9, 1954, put the figure considerably higher at $2,100,000].

The vast majority of the Montana Southern's freight and passenger traffic came from the Coolidge mining region, and as the mines there declined in the 1920s, the railroad followed suit. The railroad entered receivership in 1923 and was reorganized twice. The line was heavily damaged by a flood in 1927, and not reopened until 1930. The railroad sat mostly idle after about 1933, and the tracks were finally removed in 1940. Its formal abandonment was completed in 1941.

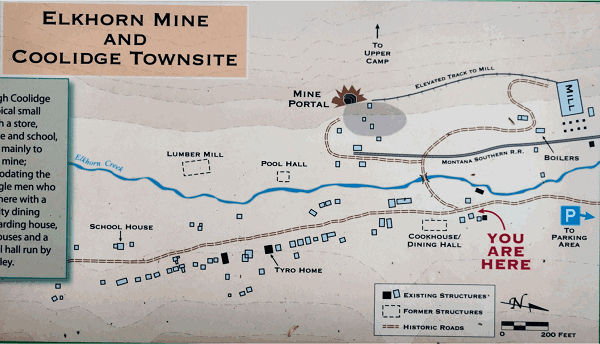

Elkhorn Mine and Coolidge Townsite map

With completion of the railroad, heavy equipment and materials for the mill could be transported to the mine site.

Work on the mill was begun immediately and the construction of a 65,000-volt power line from Divide to the mine and Coolidge was begun.

At that time, extensive exploration work had already been underway on the 68 claims (only nine were actually patented) held by the Boston-Montana Development Corporation.

Most of the major ore veins of the Elkhorn district crossed this group of claims.

Of these veins the Blue Jay had the highest grade of ore, while the Idanha, located just above the Elkhorn mill, would become the company's greatest producer with the greatest amount of ore.

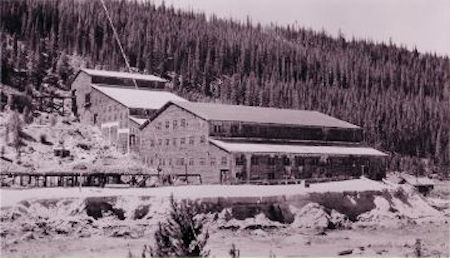

About $900,000 was spent on the construction of the mill, while another $150,000 was spent on the power line. Completed in 1922, it was the largest mill in Montana. It was equipped with steam heat, a sprinkler system, a 2500 cubic-foot air compressor, two crushers, two ball-mills, four classifiers, 16 concentrating tables, two settling tanks, two thickener tanks, a large filter and 52 electric motors to operate the mill's oil-flotation system designed by O. B. Hoffstrand. The system had the capacity to process 750 tons of ore per day with a recovery rate of 90 to 93 percent.

The complete mill

Mill at Coolidge Ghost Town, Montana

Mill after lower portion had been demolished - 1997

Mill after lower portion had been demolished - 1997

Hardware left over from the lower part of the Mill after it was demolished - 1997

Where electric power entered the mill - 1997

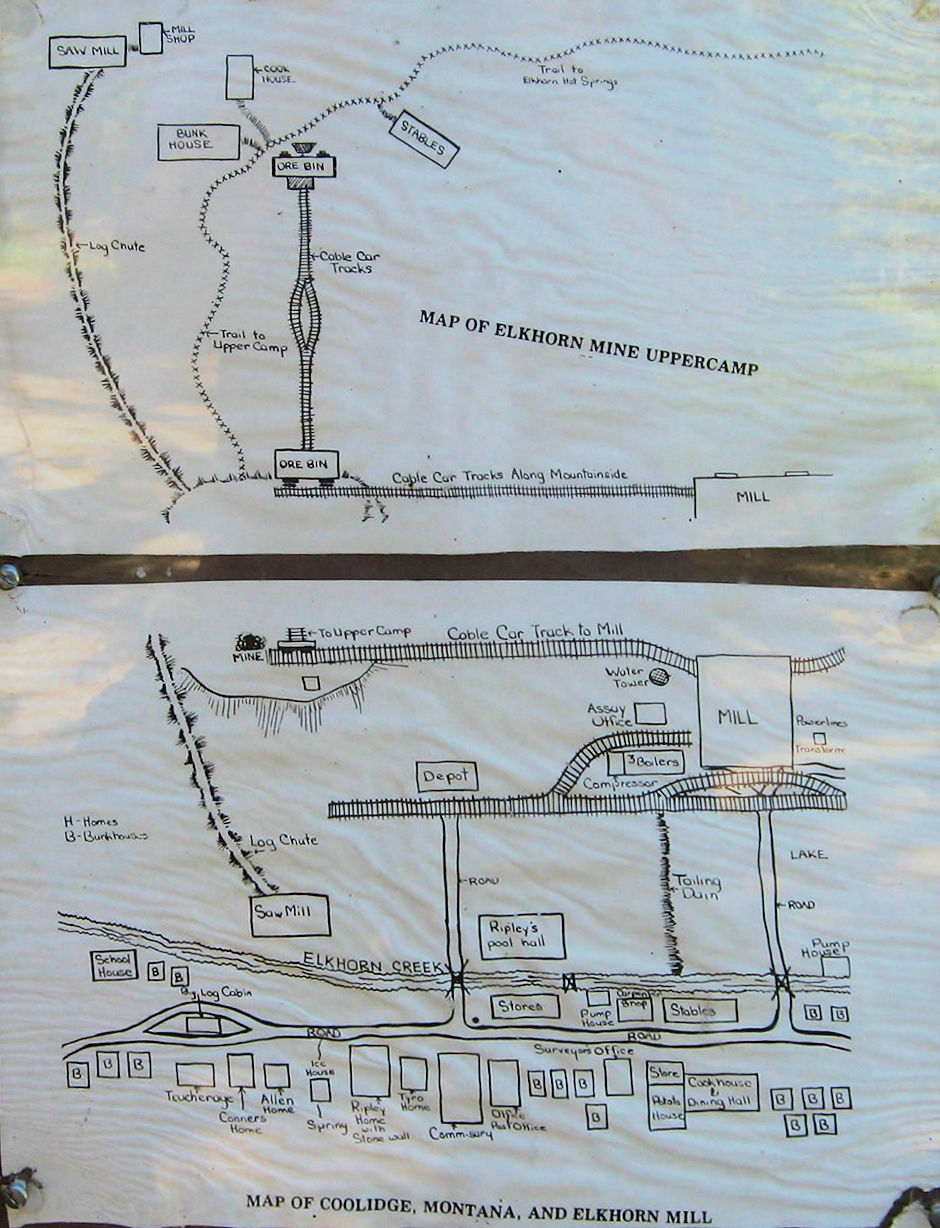

Most of the ore processed by the mill came from the Idanha tunnel at the 300-foot level, which was located at the upper camp, 800 vertical feet above the mill. Ore from the Idanha could be lowered through the No. 1 raise to the lower tunnel at the 1000-foot level where electric locomotives hauled ore cars a quarter mile to the mill.

Ore from other shafts and adits at the upper camp was brought to the mill via a rail cable car system that ran down the mountain side from an ore bin at the upper camp to an ore bin a few yards north of the lower mine tunnel portal. The tramway employed a gravity system where loaded cars going down pulled the empty cars back to the top.

The tramway had an unusual three rail track, except in the middle where the rails divided so the cars could pass each other. From the ore bin at the bottom, ore was transferred to the lower electric tramway, which hauled it to the mill.

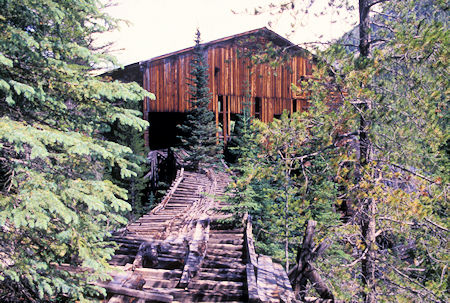

Where the lower tramway entered the mill - 1997

Lower tramway roadbed as it approaches the mill - 1997

Lower tramway roadbed as it approaches the mill - 1997

Railroad bed on the left

No forced-air ventilation system was needed for the mine workings which were adequately ventilated by natural convection currents.

Also located at the upper camp was a sawmill, three bunk houses, boarding house, six log cabins, cook house, stables, blacksmith shop, carpenter shop, hoist, and an ore sorting house.

Town Of Coolidge

Construction of the major portion of the Coolidge mining camp was begun around 1914, at the same time the mines were first extensively developed. Allen named the town after Calvin Coolidge who had become a friend of Allen's while Coolidge was still lieutenant governor of Massachusetts.

Coolidge never visited his namesake but there were reports that he had invested in the mine. When work started on the mill in 1919, large number of workers and miners moved into the camp. Initially, many of the miners lived in tents over board platforms. Later, more substantial log or board and tar paper residences were built.

A company store sold equipment to the miners, as well as food and other necessities to the community's residents. Below the store, there was a boarding house where many of the miners ate.

For amusement, miners and townspeople could visit the pool hall, run by Elmer Ripley. There were no saloons in town but liquid spirits were said to have been available from a still located near the town. Skiing and sledding were popular pastimes during the winter.

Company offices, other boarding houses and bunk houses were also part of the community. The town was equipped with electric power and telephone service although plumbing was rudimentary and few houses or boarding houses had facilities for bathing.

Elizabeth Patterson, the daughter of William Allen, who lived in Coolidge as a young girl, said that most of the town's residents went to the mill when they wanted to take a shower.

Postmasters Frank H. Tyro and Evan L. Woolman ran the post office for 10 years, from 1922 to 1932, when it was closed for good. A school district was organized in October of 1918 to operate the school for the town's 20 or so school children until the early 1930s when the town's population declined to a point where a school could no longer be supported.

Although the town had most of the amenities of other small communities, it did not have any churches. At its peak, Coolidge probably had a population of around 350. Most of the residents of Coolidge came from the local area or were from Butte and Dillon.

Elizabeth Patterson and Gilbert Dodgson, who worked at the site, both reported that there were no blacks, Chinese or other distinctive ethnic groups in town.

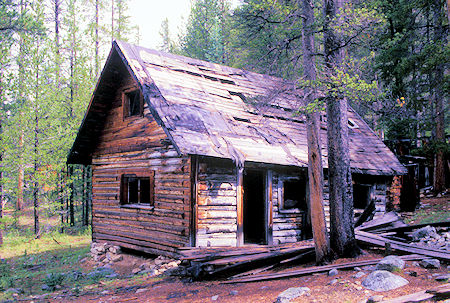

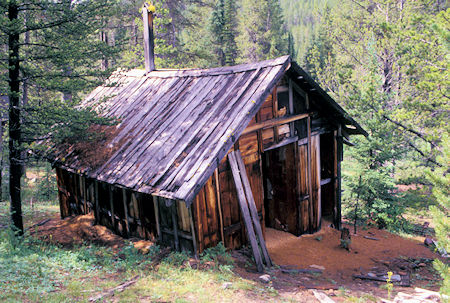

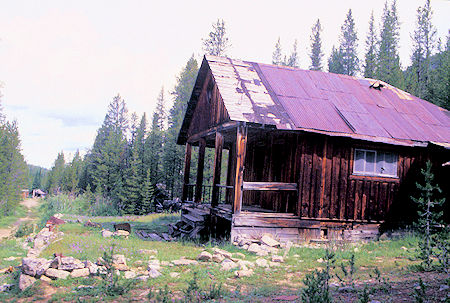

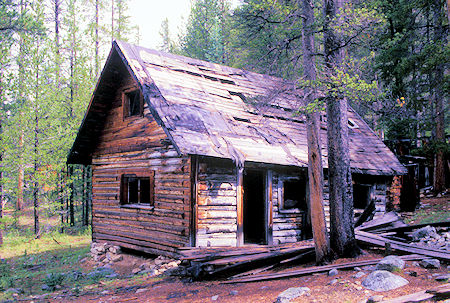

Coolidge Ghost Town, Montana - 1997

Ice House Coolidge Ghost Town, Montana - 1997

Coolidge Ghost Town, Montana - 1997

Coolidge Ghost Town, Montana - 1997

Coolidge Ghost Town, Montana - 1997

Coolidge Ghost Town, Montana - 1997

Fire hydrant Coolidge Ghost Town, Montana - 1997

Coolidge Ghost Town, Montana - 1997

Coolidge Ghost Town, Montana - 1997

Company Operations and Demise 1922 - 1950

An estimated $5,000,000 was spent by the Boston-Montana Development Company in building the Elkhorn mine project. At the start of 1922 it appeared the undertaking was about to fulfill the expectations of Allen and the other investors: the mill was a modern, efficient system ready to process the ores; the mine workings were well equipped and were being developed by experienced miners; the narrow-gauge railway was ready to haul the processed ore; and the high voltage line to power the mines and mill had been completed.

However, before the mill even went into production, serious problems began to appear. The economy had slowed down during the 1920-1921 recession and, to make matters worse, the company's bond and note issues, along with other financial obligations, came due during this same period.

These debts and obligations probably could have been met if the mines and mill had been able to go into full production but it was discovered almost as soon as the mill went into production that the veins of ore were not developed enough to supply sufficient ore to keep the mill operating at even half its capacity. A decision was then made to mine low-grade ore as well as high-grade ore but even this move failed to produce adequate ore for the mill.

Although 24,000 feet of underground workings were developed by 1925, it was not enough and the depressed economy prevented raising the necessary capital for mine development. Only one section of the mill's two parallel flotation systems was ever used and then only for three months in 1922-1923 and four months in 1925.

Within a year after the mill started production, the company was placed under a stockholders receivership. In 1923 Charles S. Murphy, president of the Montana Mine Owner's Association and I. H. Brand of New York City were appointed receivers. The company was eventually able to liquidate its debts but was forced to seriously curtail its underground development program.

In spite of this limited development, by 1927 some 120,000 tons of ore were blocked out to be mined, the ore bins were filled with 3,000 tons of ore and six cars of concentrates were ready for shipment from the mill. But then, the final blow in the series of misfortunes experienced by the company occurred in June of that year when a Montana Power Company dam on Pattengail Creek broke, flooding the lower Wise River valley and washing out 12 miles of the Montana Southern Railroad's tracks and several of the line's bridges across the Big Hole River.

The line was repaired by 1930 but by then the Great Depression had begun and metal prices had declined to a point where it was not possible for the company to resume production.

The company was reorganized on May 17, 1933 as the National Boston-Montana Mines Corporation. In 1944, it became the Boston Mines Company but it was still unable to revive the operation and by the end of the 1940s most of the company's deeded properties were acquired by Beaverhead County in lieu of taxes.

As head of the National Boston-Montana Mines Corporation, William Allen continued for the next two decades to try and revive the Elkhorn mines. Although he lost his personal fortune in the enterprise, he continued to believe that the mines were a potential bonanza until his death in 1953 at his home in Wise River.

At their peak, the mine and mill employed 250 men, yet a total of only 26,000 tons of ore was mined from 1921 through 1924. Another 20,000 tons was produced in 1925 but from then on, only a few tons were mined sporadically during the years 1935-1937, 1939, 1942, 1948 and 1953.

Total production from the Elkhorn mines was 52,385 tons of ore and from that, 8,900 tons of concentrates were produced for shipment to smelters at Tooele, Utah and East Helena, Montana.

The concentrates yielded 851,725 pounds of lead, 4,100 pounds of zinc, 370,799 pounds of copper, 180,843 ounces of silver and 1,013 ounces of gold. In 1949 the company reported the total production of the Elkhorn mines amounted to $375,000. This figure, however, could not begin to match the estimated $5 million that was invested in the project.

In 1981, the Elkhorn mines were bought by Timberline Minerals, Inc. who did some exploratory prospecting work on the site for the next three years. They reported that there was good potential for silver, as well as tungsten and molybdenum, but no significant production was reported during this period.

The primary operation which dwarfs all other mining features in the Elkhorn District is the Elkhorn mine and mill and the associated community of Coolidge. The lower mill was torn down for salvage sometime in the 1970's, prior to my visit in 1997 [the 18-inch wood beams were reported to have been used to construct a restaurant in Idaho Falls].

Demolition of the upper section of the mill was done about 1999 as a safety measure. The other remains are of interest as a historical site and administered by the Beaverhead-Deerlodge National Forest.

Many of the mine buildings are standing, primarily at the upper mine, and the other remaining features are sufficiently intact to allow a good understanding of the mining and milling operations. Coolidge and the mine area contains the remains of over 100 features and structures ranging from depressions to standing structures.