Loading Navy rescue helicopter

So maybe you think you've done it all in these mountains, recreation-wise. You've hiked every conceivable trail, climbed the classic routes, spent weeks in the backcountry, bouldered, skied, snowboarded, and mountain-biked to the limits of your fancy. You know that you've got a good head on your shoulders, that you've got some skills.

But in introspective moments, you notice you're getting a little weary of the self-absorption and one-upmanship of the adrenaline set. You've got an abundance of energy, aptitude, and good judgement -- but what does it all amount to?

Perhaps it's time to consider another "lifestyle" alternative. Mono County's volunteer search and rescue team is holding its annual recruitment meeting, and they're looking for a few good men and women.

What Is SAR?

In Mono County, as in most of the counties of California, the search and rescue team is comprised of volunteers. The Sheriff's Department oversees the team, but all members participating in rescue operations do so for free. Operations leaders here -- the people who coordinate rescurers, equipment, and interagency support -- are usually volunteers too.

Mono County's search and rescue (SAR) team is involved in approximately 30 operations a year. The busiest months are July and August, when there are 10 to 12 operations a month on average. In the winter months, there are about four operations a month.

"We aren't just rescuing mountain climbers or hikers," said Greg Enright, a long-time SAR member. Rescue operations include just about every imaginable situation.

"We've helped drivers out on the highway; and we've helped people who were out for a little walk when something went wrong. Some of the people we've rescued were in awesome shape, and yet something happened to them anyway; others were in lousy shape and had no business doing what they were doing. They're not all out-of-towners either; some have been locals."

SAR team members are a special, but not necessarily a specialized, breed of mountain folk.

"We're all volunteers -- we don't get paid," said Jim Gilbreath. "We do this because we like to, and we have fun."

"You don't have to be a climbing hero to be useful on the team," he explained. "We'd like to attract people with special skills -- computer, radio, GPS, navigation skills -- but you don't need to know [those skills], because we'll teach them."

Gilbreath said that a certain level of fitness is necessary, but anyone who is a "competent backpacker" already has the basic skills necessary for the team.

"We want people who feel at home in the mountains," he said., "but not necessarily [people who are] super technically-oriented."

Enright said the SAR team also needs people to help organize operations, "people who are very good at doing organizational stuff" -- someone who can "sit in a car, order up helicopters, do all the logistical things necessary during an operation."

A good candidate, Gilbreath added, will be "someone who wants to be part of the team who has the time to do training, and is available to go on calls."

Winter and Summer

Search and rescue member Pete DeGeorge practicing swiftwater rescue techniques

"There's nothing like going on a rescue and saving someone's life," said Victor Aquirre, "or even helping someone to back out of a difficult situation."

One of the most common winter operations for the SAR team involves finding skiers or snowboarders who have gone down the back side of Mammoth Mountain. Disoriented by white-outs, or led astray by "the allure of making fresh tracks," these people -- as many as 15 during the 1998/99 ski season -- usually ski down towards Red's Meadow, ending up either at Pumice Flat or Sotcher Lake.

The SAR team's procedure in these cases is to send a few rescuers on skis down from above, while others on snowmobile take the Devils Postpile road the long way around (unless the avalanche danger is high), and try to attract the wayward skiers' or boarders' attention by means of a megaphone and lights.

Aguirre, the team treasurer, said that they had to extricate fewer skiers/snowboarders from the back side this year because the Mountain "put out a lot more signs [indicating the limits of the Ski Area]" than in the past.

As for the more gruesome and upsetting aspects of mountain rescue, Aguirre said there were modest satisfactions in this as well.

"[When we] recover people who have died in the backcountry, that gives the family closure," he explained.

Tracking and More

Sallee Burns, who works with a tracker dog, said that the search in June for an elderly man with Alzheimer's was one of the most memorable operations of 1999.

Five dog teams were involved on that occasion in the Bridgeport/Twin Lakes area, she recalled, and "the search went on for quite a while."

Greg Enright, who was operations leader, agreed: "I've see multi-day searches where searchers get kind of bogged down, and start thinking,'Oh no, this guy must have left the area.' But everyone who was there [at the Bridgeport/Twin Lakes rescue] stayed focused, and gave 110 percent, 120 percent."

"The area was heavily wooded, and hard to search. It turned out the victim went way beyond were we expected."

The missing man's body was found later by hikers, up a drainage southwest of Twin Lakes.

Tracking training

Enright, who has been involved in search and rescue for 20 years, teaches team members how to track lost people. By reading footprints and other signs, he said, a good tracker can tell all kinds of things about the person he or she is following, including weight, fitness, level of fatigue, and preference for the right or left foot. Enright said he can even tell the mood -- cautious, determined, angry, distracted -- of a walker.

"It's interesting," he said, "how differently people walk in the same shoes."

Enright said that search and rescue teams use "profiles" to help them predict where lost individuals are likely to end up. But he's noticed that people who get lost in the High Sierra often wander miles and miles from where they started.

"It seems like when people get lost," he said, "all of a sudden their horizons expand 10-fold. It's like everything's magnified up here."

A Quiver Full of Skills

Tracking, Enright said, is only one arrow in the team's quiver.

"It's one of those things you practice a lot and you only use it a few times a year."

"You have to aid in whatever way you can," he said. "We have so many different disciplines represented on the team. You never know whether it's going to be up your alley, or up someone else's alley. But [most rescues do not involve] just walking out, throwing someone on a stretcher and walking back."

Dramatic rescues on high and exposed cliffs occur infrequently. "You may need the ropes and rock-climbing skills only a couple of times a year," Enright explained, "but when you use them they have to be sharp."

Dog trackers and their trainers, he said, are an example of another SAR team discipline that requires constant work to maintain a high level of preparedness.

"It's incredible how much dedication those dog trainers have," Enright said. "But all that [dedication] pays off when -- even if only once in a career -- someone gets saved."

SAR members receive training in tracking and search techniques, ropes and knots, search protocols, map and compass use, snowmobile use, avalanche analysis and rescue, ice rescue, and more.

"I Wanted to Be on This Team"

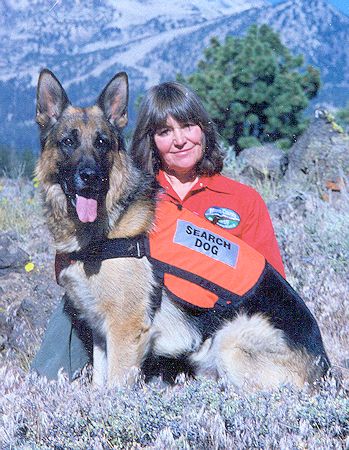

Sallee Burns with her search dog Trapper

Of the 45 people currently on the SAR team's active call-out list, nine are women.

"Search and rescue is a field that women should excel in as well as men," said Burns, who has been a team member for about eight years.

"Primarily, at first, I wanted to be a dog handler," she said, "but in going through the training, I discovered that what I wanted even more was to be on this team. I decided that this was something to do no matter what -- even if the dog didn't become mission-ready."

Dori Leyen, who after just over a year is a "candidate" for the team, said she is "90 percent of the way there" with her training, and has participated in seven rescue operations.

"It kind of hooks you," Leyen said. "You feel really good about helping someone."

Although there's no minimum time commitment, she said, "The more you commit to it, the more you get out of it, and the more you can help."

"You're with a group of people who are all caring people," Leyen said. "You truly do get that feeling. [Team members] really look out for each other."

Rescue at Half Moon Pass

One of the stand-out operations of the summer of 1999 was the rescue of Eric Brower at Half Moon Pass, near Rock Creek Lake.

Leyen, who participated in it, said there was a sense among the rescuers that any one of them could have been in Brower's place.

"He wasn't doing anything that all of us don't do all the time," she said.

The rescuers [including members of both Mono and Inyo County SAR teams) lowered Brower on belay by stretcher to a flat place, and then kept a fire going through the night to try and keep him warm. A helicopter came at first light.

"That's pretty incredible when you're there waiting all through the night," Leyen said, "and then you hear the sound of the helicopter through the canyon."Looking back on the rescue at half Moon Pass, Enright said he was struck by "how many people it takes to help one person who's been injured [in the mountains]."

He recalled that "a lot of brute force, and technical systems, and a lot of people" were required to get things done on that night. One team stabilized Brower, another brought up more medical gear, another bushwhacked a stretcher up the valley from the road.

"Sometimes when someone's in really dire straits," Enright said, "it can take as many as 30 people in the field [to help them]."

Priceless Service, Low Costs

It costs Mono County a mere $14,000 annually to operate the SAR team.

The team uses several rescue vehicles owned and maintained by the County: a van, which is staged in June Lake; a utility truck with a trailer for extra equipment, staged in Mammoth; and two snowmobiles for winter use.

When helicopters are required to lift out victims, they are called in most often from Fallon Naval Air Station.

"We have a great working relationship [with Fallon]," Enright said. "They regularly do things that are seemingly beyond what any helicopter crew should be able to do."

California Highway Patrol helicopters, out of Fresno or Auburn, are also available for rescues; and there are a couple of other options as well if those helicopters are engaged.

The cost of rescues can sometimes be recouped by Mono Couty, but "SAR [itself] never charges anyone anything." Enright said. If a rescued person is from out of county -- but from within California -- Mono County can forward the bill to the county of origin.